A New Wave of Prominent African-American Retirees is Enriching and Changing Our City.

A welcome wave of African-American retirees is making its mark on our city.

On a chilly Saturday night last February, the valets at The Ritz-Carlton, Sarasota were scurrying around as usual, parking the long line of shiny Lexus, Mercedes and BMW lined up for yet another black-tie gala. What wasn’t so usual was the crowd. More than 500 guests were arriving for the inaugural fund raiser for the Sarasota chapter of the black fraternity Gamma Xi Boule’, and about half of them were African-American. That’s an unfamiliar sight in Sarasota County, where 5 percent of the population is black (the national average is 13 percent) and only a smattering of African-Americans appears at most high-profile events. But it wasn’t just the range of skin colors that felt novel. Many of the African-Americans in the ballroom were recent newcomers, part of an influx of retired black professionals who are beginning to make a mark on their new hometown.

A New Wave of Prominent African-American Retirees is Enriching and Changing Our City

Black professionals are not new to Sarasota, of course. There have been black teachers, doctors, attorneys and business people here for generations. Many of them were born and raised here, and they retire here as well. But the new arrivals have increased black professionals’ numbers and visibility. “It’s a definite critical mass,” says Eleanor Merritt-Darlington, 82, an African-American artist from New York who has lived in Sarasota since 1982. “I’m glad to see it happening, and I’m really pleased to see Sarasota grow up.”

The newcomers include college professors and administrators, doctors, corporate executives, ambassadors, politicians and journalists. They’ve lived in major cities, mainly in the North and Midwest, and enjoyed impressive careers that have taken them all over the country and world. They come with wealth, talent, experience and connections.

The newcomers include college professors and administrators, doctors, corporate executives, ambassadors, politicians and journalists. They’ve lived in major cities, mainly in the North and Midwest, and enjoyed impressive careers that have taken them all over the country and world. They come with wealth, talent, experience and connections.

Among their ranks are Emmy- and Peabody Award-winning journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault and her husband, Ronald, a retired banker; James A. Joseph, former ambassador to South Africa and his wife, Emmy Award-winning television journalist Mary Braxton-Joseph; former Detroit Mayor Dennis Archer and his wife, retired Michigan District Court Judge Trudy DunCombe Archer; Donald Reaves, a director of Amica Mutual Insurance and formerly the CFO of Brown University and the University of Chicago; Robert Wood, a past CEO of Chemtura (formerly Dow) Corporation and now a board member of the U.S. Olympic Committee; and retired Harvard Business School professor James Cash Jr., who has had board positions with Microsoft and Wal-Mart and is a member of the Boston Celtics ownership group.

Why are they coming? Most say that’s simple: It’s for the same reasons other successful people retire to Sarasota.

“It was the perfect mix of everything we were looking for,” says Michelle Davis, 57, who moved to Sarasota from New Jersey five years ago with her husband, ABC executive Preston Davis—the first black divisional president in the ABC network. (He died in 2013.) “It had direct flights to Newark at the time, an excellent hospital system, close proximity to the beach, good restaurants, arts and theaters. The icing on the cake was no state income tax.”

Greg McDaniel, 64, who retired as president of Chemtura AgroSolutions, moved here in 2011 with his wife, Hannah, who was the director of fund development for the Indianapolis Neighborhood Housing Partnership. They had considered Charleston, Savannah and Hilton Head, but St. Armands Circle reminded him a bit of southern France, where his work often took him. “But it was more affordable here,” he says. “And Sarasota had the arts, jazz and civic activities. It’s a small town with big-city attributes.”

And McDaniel found one more asset. “I caught the bug to get involved in civic affairs again after being so involved in my corporate career,” he says. Active in the local Boule chapter and its scholarship program, McDaniel says, “Sarasota is a city where you can make a difference.”

Reaves, the university CFO, and his wife moved here from Vero Beach last year. “Being African-American, there was a big cultural void there,” he says. “[In Sarasota], there’s a welcoming atmosphere for African-Americans. We’ve lived all over—Boston, Chicago, North Carolina. This is the best move we’ve ever made.”

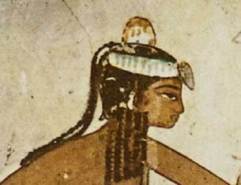

Black Muse: Powerful African American art at Art Center Sarasota

Sarasota County’s black population grew by 3.5 percent from 2010 to 2014, while the county’s overall population grew by 2.9 percent. Many of these black newcomers, like many white newcomers, are retirees—all part of the massive wave of baby boomers across the country who are now retiring, and in many cases, moving south. But their relocation to Sarasota is not only part of the baby boomer demographic shift; it’s part of a larger pattern of African-American migration in the United States.

Starting in the 1970s as just a trickle, black people began to move out of the Northern and Midwestern cities where they’d fled decades ago in hopes of finding a better life. That first exodus, between 1915 and 1970, saw 6 million African-Americans pack up and head North to avoid the poverty, violence and Jim Crow laws of the South.

That movement is often called the Great Migration, something journalist Isabel Wilkerson, who spoke in Sarasota in 2015, chronicled in her Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Warmth of Other Suns.

Now those Northern cities and states are losing African-Americans of all ages, from young professionals to retirees, to the Sunbelt. For young and working people, no matter what their color, economic opportunity is the major attraction. The South is growing and prospering while many Northern and Midwestern states are losing population and jobs. But the South also holds emotional ties for many African-Americans. They have family and memories in places where the tea is sweet and the air is soft and languid. In their retirement years, African-Americans often want to go back to those roots.

Members of the West coast Black Theatre Troupe

As demographer William Frey documents in his 2015 book, Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America, this latest African-American migration—called the “reverse migration”—will change the United States politically, culturally and economically. “It’s a large, broad-based movement that’s been going on for a long time and it’s come into its own,” he said from his office at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.

But Florida, he says, is not a traditional homeland for African-Americans in the way that Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama are. “I would say that [the arrival of new retired African-Americans in Sarasota] is a part of this movement but not the core. Wealthy, well-connected elites are going to Florida, and this is a strand of that broad black movement.”

Bernard and Lois Watson moved here from Philadelphia, where he was a well-known educator and philanthropic leader.

Retired educator Lois Watson moved to Sarasota from Philadelphia in 2002 with her husband, Bernard, now 87, who is well known in cultural circles for relocating—some say saving—the legendary art collection of Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation when he chaired the foundation’s board. (See “The Remarkable Doctor Watson” in our Platinum 2015 issue.) Lois Watson remembers when a friend, Sarasota orthopedic surgeon Randall Morgan, told her to consider retiring here.

“I thought he was nuts,” she says. “Florida was never on my list. Historically, it did not have a welcoming atmosphere for African-Americans.”

But when the Watsons visited in 1996, they liked what they saw. “It was beautiful,” Lois Watson says. “People were warm and friendly. And because Bernie was traveling a lot, I was here, and I found other people with the same interests as me.”

Even before the current wave of African-American baby boomers, some black retirees found their way to Sarasota. And back in the 1980s, one of the main reasons they came was a dynamic black real estate agent, the late Alice Peggy Hairston. Her former friends and clients say she was known as the Pied Piper for her ability to lure prominent out-of-state African-Americans to Sarasota.

Hairston worked in accounting for a law firm in her native New York before moving to Sarasota in the early ’80s with her husband, Robert, says Sarasota attorney Sylvia Taylor, who handled most of Hairston’s closings. Outgoing and vivacious, Hairston had a huge network of friends and relatives in New York. “She was an extremely social person and very caring,” Taylor says. “And she could sell anything. She started with her relatives and then all of her contacts.”

Black Theatre Troupe

Many people Hairston brought here knew each other from their summer homes in Sag Harbor in the Hamptons and Martha’s Vineyard, says Taylor. That’s still true today. Journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault, 74, who bought a home in Sarasota in 2013, says she and her husband often run into people they know from Martha’s Vineyard, where they spend their summers. (The town of Oak Bluffs on the Vineyard has long been a vacation retreat for wealthy black people.) “We call Sarasota Martha’s Vineyard South,” jokes Hunter-Gault, who says she and her husband enjoy the town’s arts and restaurants (they own a vineyard in South Africa). She also has spoken at events for nonprofits such as New College and the Community Foundation of Sarasota County.

James Taylor, now president of Boule and a financial planner, came to Sarasota in 1982, but he wasn’t a retiree lured here by realtor Hairston. Instead, he was something rarer in those days—a young African-American banker from Ohio who came here to work for Barnett Bank. “When I went into a restaurant every head turned as if no one had seen a black person walk into a restaurant before,” he recalls. Still, he adds, “I’ve never had anyone approach me antagonistically or offend me because of race issues since I moved here,” and he says he felt like he belonged from the beginning.

Like many other new retirees, Michelle Davis decided to start a business–Zumba Sarasota–after she moved here from New Jersey.

Many of the African-Americans retiring to Sarasota today are pioneers, the vanguard of their race to move out of poverty and away from centuries of enforced segregation. They were often the first in their families to go to college, to become professionals and to achieve upward mobility.

It took courage and determination. Hunter-Gault, for example, faced enormous hostility as the first of two African-Americans students to enroll at the University of Georgia in 1961. Mark Jackson, a 68-year-old retired strategic marketing director for global business customers for AT&T (later Lucent Technologies), remembers interviewing at New Jersey Bell Telephone when he was a college student and initially being offered a job as janitor rather than on a professional track. His wife, Penny, started out as an AT&T operator before becoming international data offers director for Lucent and traveling all over the world.

Bernard Watson was one of the few black students in the 1960s at the University of Chicago, where he received his Ph.D. As an undergraduate at Indiana University, he was threatened with a gun for advocating for racial equality, an incident that only strengthened his commitment to civil rights activism. He went on to a distinguished career as an educator and college administrator and was appointed by three presidents—Lyndon Johnson, Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton—to serve on various councils.

“The worlds are very small,” says Dr. Lisa Merritt, Eleanor’s daughter, of the rarified, intimate circle of African-American professionals who have made it. Merritt moved here 10 years ago, bringing her Multicultural Health Institute, which she founded in California. “We travel in small circles,” she says. “Everybody knows everybody.”

Journalist Mary Braxton-Joseph first met Merritt at a women’s empowerment conference in Cape Town in 1997, when Braxton-Joseph’s husband was the ambassador to South Africa. Braxton-Joseph also met Doris Johnson, a retired black medical administrator from Texas, in South Africa during that time. This January in Sarasota she bumped into Johnson at 941CEO magazine’s Unity Awards luncheon. “Talk about a small world,” she says. “All roads seem to lead to Sarasota.”

Many of the African-American professionals who retire here are also connected by their membership in black fraternities and sororities, and organizations, such as The Links, an African-American-only service organization for women. Boule, which held the gala at the Ritz-Carlton, is an invitation-only black fraternity for high-achieving men.

These groups play enormously important roles in the lives and careers of black professionals. “You have to understand our history,” says Bernard Watson. Decades ago, black people were barred from joining many organizations, which limited their opportunities to network, get involved in civic affairs or socialize. They couldn’t meet in most restaurants or reserve or rent most public or private space for meetings. Black-only groups provided support, networking and a wide circle of friends who understood each other’s aspirations and obstacles.

“When you traveled you couldn’t go to hotels, so we stayed at each other’s homes,” Bernard Watson remembers.

Many African-Americans remain active in their college fraternities and sororities throughout their lives, drawing on them as a source of empowerment and advancement. And when they relocate, they often seek out their Greek brothers and sisters. These organizations make it easier to connect and get involved. “For us,” says Lois Watson, “these associations continue our commitment of service to the community.”

ASALH—the Association for the Study of African American Life & History—is often the first meeting place for new African-American professionals and retirees in Sarasota. The local chapter, Manasota ASALH, Inc., which just celebrated its 20th anniversary, is the largest of the 27 chapters in the nation, with 187 members. It’s bigger than chapters in Chicago, Atlanta and Detroit. Former AT&T exec Jackson, the current president, says that five years ago they had only about 50 members. “Everyone who comes here passes through ASALH. We’re growing exponentially,” he says.

Because of its clout and numbers, the chapter brings in big national speakers for its annual dinner. In 2015 it was author Wilkerson. This year it was historian and ASALH’s national president, Evelyn Higginbotham. Two of the attendees were Dr. Valerie Montgomery Rice, the dean of Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, and United States ambassador to the United Nations and former Congressman Andrew Young Jr., who were traveling the country to raise money for the medical college. When Rice, whose son attends Ringling College of Art and Design, spoke at a fund-raising gathering at Florida Studio Theatre that weekend, she told the 200 prosperous-looking African-Americans in the crowd that she had no idea there were so many of them in Sarasota.

These newcomers have settled all over Sarasota, at the Ritz-Carlton, in Lakewood Ranch, University Park County Club, The Oaks and everywhere in between. But they haven’t chosen to live in Newtown, the historically black and poor neighborhood in Sarasota.

Tensions exist between the two communities—the black old-timers who have lived for generations in a segregated neighborhood and the new black bourgeoisie who have lived, worked and mixed socially with whites for their entire careers in major urban centers.

“When the group first started to move here,” says Ed James, the host of WWSB’s Black Almanac and a vocal, longtime activist for the Newtown community, “the locals and the newbies did not get along. The locals wanted to know, ‘Who are these people coming here when they don’t know us and telling us what to do?’ On the newbie side, some thought we were the dumbest people in the world.”

Black Theatre Troupe

Like other retirees, new African-Americans can take time to get their footing in the community and find where their passions and talents will lead them. Some—like legions of other baby boomers—are starting new businesses that reflect their personal interests and passions. Michelle Davis had been a fitness trainer up in New Jersey. After her husband died, she partnered with another woman to start Zumba Sarasota, a dance and fitness studio.

Bbp 1275 hqhe4r

Like many other new retirees, Michelle Davis decided to start a business–Zumba Sarasota–after she moved here from New Jersey.

Others have plunged into local causes and organizations. Carol Buchanan, a former educational administrator from New York, moved here 23 years ago with her late husband, Carroll. Now 87, she started the Gulf Coast Community Choir and sits on the boards of Florida Studio Theatre, Planned Parenthood of Southwest and Central Florida and Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe.

Michele Redwine, an artist and educational consultant from New York, moved here in 2005 with her late husband, Preston, an executive at I.B.M. She immediately found places where her expertise would be useful, including Art Center Sarasota, Gloria Musicae and Realize Bradenton. Today she serves on the board of the Hermitage Artist Retreat and the Ringling Museum.

Both women have made it a mission to attract the newer African-American transplants onto boards and into the community. “I’d love to get more of these folks involved,” says Redwine.

Chief Twelfth Judicial Circuit Judge Charles Williams, who has been an important voice in race relations in Sarasota, says the arts community is feeling the effects of these newcomers. “It used to be that they were here only three months; now more of them are full-time. They’re having an impact. All of a sudden, [we’re seing more] plays dealing with race and diversity. And these new people are donors. They go to the ballet, the theater,” he says.

And each new discovery can lead to something else, deepening connections to the community. James Stewart and his wife, Caryl Sheffield, both Ph.D. college educators from Pennsylvania, retired to Sarasota last fall, attracted by the sunshine, palm trees and laid-back atmosphere. They play tennis, golf, play cards and go to the beach. “But we also knew there was a reputation of African-American culture here,” says Sheffield. “Finding out about the Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe was major for us.”

In January, the Arts and Cultural Alliance of Sarasota County exhibited some of their collection of African-American art. Stewart, a national past president of ASALH, says he hoped the exhibition would connect not only with art lovers, but with the Newtown community. “The art exhibit is part of our African-American history,” he says. “There’s an effort to preserve Newtown and I’ve offered my services. I’d like to do something there.”

Sarasota Wedding at Ritz Carlton

Regardless of how much they may choose to get involved, these newcomers, by their very presence—on our tennis courts and golf links, in restaurants, supermarkets and on the beach, in political meetings and at charity fund raisers—are already making Sarasota a more diverse and interesting place.

“I used to be the only person who looked like me in the theater,” remembers artist Merritt-Darlington. “We’re becoming a community we can all be proud of.”

May 2016 Sarasota Magazine.